FIRST

STEPS IN ‘O’ GAUGE.

Fifteen

year old Tom Lewis builds a Tower Collection Andrew Barclay 0-4-0ST beginners

kit.

Tom Lewis is fifteen and lives with his parents in the West Midlands. He was given a Hornby train set when he was six which he enjoyed for the next few years. Inevitably computers and video games became more attractive and the train set was discarded. This article tells of the rebirth of his interest and his successful first attempt at building an ‘O’ gauge locomotive.

My

Dad got interested in ‘O’ gauge about four years ago. Like me he had had a train set as a child and had retained some

interest. He started by building a few

Slaters and Parkside wagons and finally bought a Tower Collection Class 02

diesel shunter kit. This was supposed

to be a kit suitable for complete beginners and it must have been good because

he managed to build it without any problems.

He went on to build a couple more larger diesels and the house started

to fill up with ‘O’ gauge.

Finally

I decided to take up the hobby again.

Dad likes diesels but I don’t. I

wanted to build a locomotive but was only interested in steam outline. Given the high cost of kits (especially if

you are still at school!) I had to get it right first time.

Cheapest

option appeared to be a Mercian “Winnie” starter kit. Priced at £69.00 it seemed to be a bargain. To this has to be added wheels, gearbox,

motor and couplings bringing the total price up to about £142.00. My Dad took me to the ‘O’ gauge Guild event

at Chippenham and I was able to look at the kit. Although I liked the locomotive type the kit is mainly etched

brass with some whitemetal parts. It

would obviously require mainly solder construction and I wasn’t sure if I was

up to it. I decided to continue

looking.

A

friend of my fathers showed me a Springside Pug he had built. He told me the kit was supplied complete

with wheels, gears and motor and I could expect to pay around £175.00 for

it. It was useful to me being able to

examine the finished model. All the body

parts were made of cast whitemetal so could be glued instead of soldered. However it appeared rather complicated in

it’s construction so I decided against it. I then got chance to see other

models of similar price in the Springside range by looking at a website. I am told the Manning Wardle and the Coffee

Pot are both easier to build but I just didn’t like the prototypes.

The

next exhibition Dad was taking me to was the Association of Larger Scales

Railway Modellers event at Reading.

Prompted by my family I rang Tower Models and asked them if they were

attending and if they would have a sample of their Andrew Barclay beginners

kit. They said they would be there and

that they would have a built but unpainted sample of the locomotive on display

that I could handle.

A

week later at the exhibition I had chance to examine the finished item and to

go through the instructions of the kit.

The instructions seemed very well detailed and I was impressed by the

completeness of the kit. It even

included the Allen key for fitting the wheels.

What is more, if it was as easy to build as the Class 02 diesel then it

should be no problem. After all, my Dad

had succeeded, so why shouldn’t I?

It

took all my birthday money from my parents and family to buy the kit which was

priced at £179.95. Dad told me I could

use his solder, soldering iron and glue so that would save me a few

pounds. I also knew I could rely on

help from his friends at the model railway club if necessary. I resisted the temptation to start it as soon

as I got home and waited until the following weekend before commencing building

work. I spent a few hours in the days

between to read the instructions and familiarise myself with all the parts.

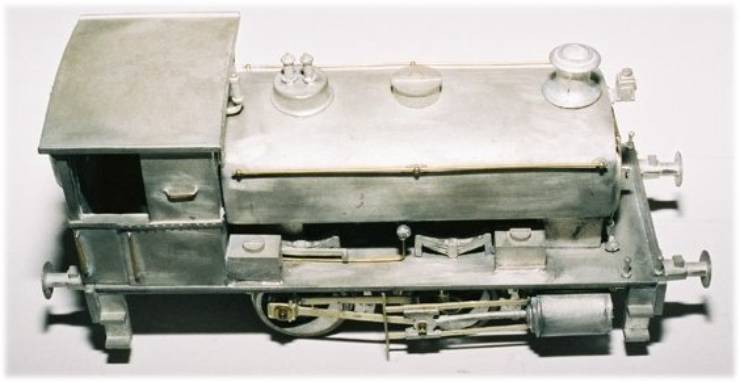

The

following Saturday I decided to start work on the building. The kit came with twelve pages of

instructions including a number of exploded diagrams so I began by re-reading

them again. Tower Models had described

the kit to me as a screw and glue type kit that requires minimum amounts of

soldering. All the body parts could be

glued together with two part epoxy resin.

Only pickups, the wiring to the motor and a few small parts would need

to be soldered.

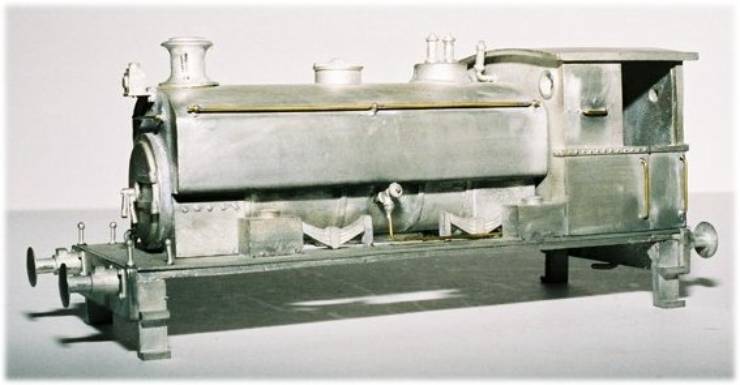

The

instructions suggest you start by building the body. The saddle tank is cast in one piece in pewter. Everyone tells me

this is better than whitemetal because it is stronger, melts at a much higher

temperature and contains less lead. The

saddle was cleaned up with a smooth file but was basically free from

flash. It was now necessary to drill the

holes for the handrail knobs. To be

more accurate, you have to deepen the holes using a 1.4mm drill. Dad let me use his Minicraft electric hobby

drill. I managed to deepen all eight

holes without breaking the drill bit.

The handrails can then be fitted in place. Dad told me it would be

better to solder the handrails in place but I fixed them with careful use of

superglue. The handrail wire was then

fitted through the knobs and again I used superglue to secure them. The chimney, water cover and whistle are now

ready to be glued in place using epoxy resin.

The

lower half of the boiler is also cast in one piece. The smokebox door handle needs to be fitted to the smokebox door

after deepening the hole with a 1.9mm drill.

The boiler, saddle and smokebox can now be all glued together, again

with epoxy resin.

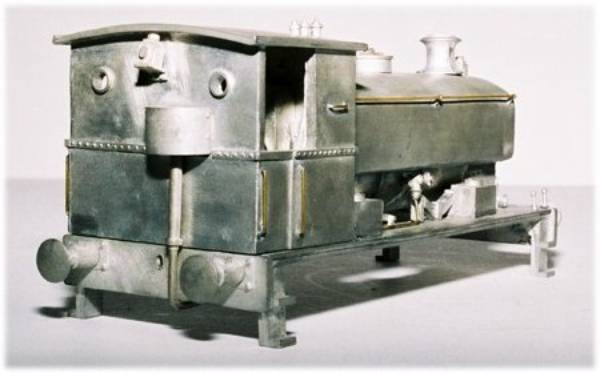

The

cab is cast in one piece. A few small

parts have to be glued to it such as the brake handle and cover. The backhead is a separate piece and has to

be glued in place with the regulator fitted .

it was now necessary to fit the buffer beam to front and rear of the

footplate. I would have glued this but

an interfering father stated it was time to test my soldering skills. He argued that the buffer beams carry the

couplings and hence need to be securely fixed in place. Maybe he had a point but I was still a

little nervous.

Out

came the soldering iron, a liquid flux and some 70 degree melting point

solder. As Dad pointed out if I made a

mess of it I could drop the parts into boiling water and it would melt the

solder but not the parts. That was, as

he pointed out, providing I didn’t burn a hole in the metal, as was the fact I

was not allowed anywhere near Mum’s best pans should I make a mistake during the

soldering.

The

soldering iron was allowed to heat up, liquid flux applied to the parts, the

tip of the iron and the solder to be used.

I applied the iron to the solder, melted a bit onto the tip of the iron

and applied it to the joint between the bufferbeam and footplate.

Amazingly

it worked, it really was that simple. A

little more solder was applied to give the joint strength and then the buffer

beam at the other end of the footplate was soldered in place. Feeling more than a little pleased with

myself we took a coffee break.

Returning

to the job I then glued parts such as the tool boxes and reversing lever in

place. With the footplate completed it was laid aside. The handrails are now

fitted to the cab sides, following more drilling with a 0.7mm drill. The cab, assembled saddle and boiler all

screw fit onto the footplate. The

buffers, steps and couplings can now be fitted.

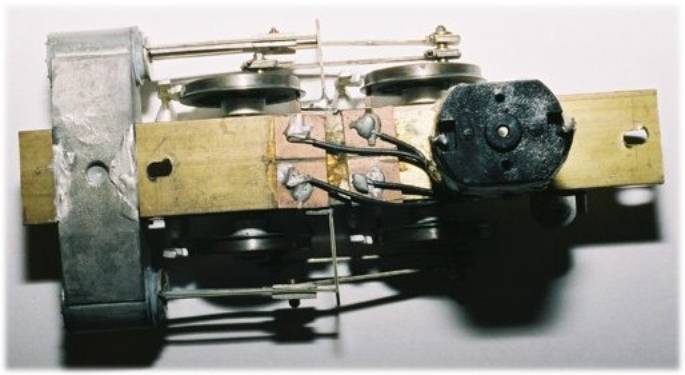

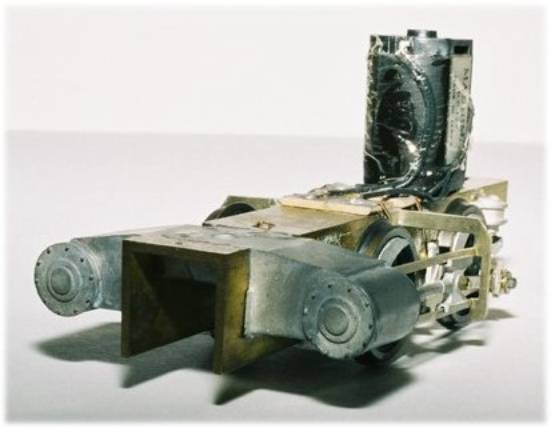

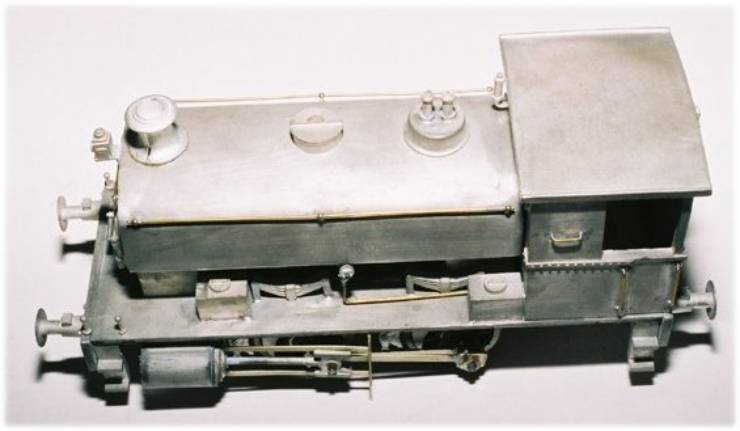

Four

hours after opening the box I had finished the body. I decided it would be better to quit while I was winning so I

decided to leave the chassis until the following day. The chassis consists of a preformed heavy brass channel with all

the holes already drilled. The wheels

and axles supplied with the kit are Slaters.

The wheels are assembled on to one side of the axle, then passed through

the chassis and the other wheel fixed in place. A balance weight is then stuck onto the wheel. Crankpins, which are also supplied with the

wheels, need to be fitted before the wheels are fixed to the axles

The

complete cylinder block is a casting. The cylinder end caps have to be fitted

in place and the whole assembly soldered to the chassis channel. As I was now soldering pewter to heavy brass

this was a first for me. Lots of heat, plenty of flux and crossed fingers all

must of helped because it worked. The

gear had already been fitted to the axle when the wheels were mounted to the

chassis. I left the grub screw loose so

I could settle the position of the gear once the motion was in place. Tower Models had told me to slightly

elongate the holes for the motor screws which would allow adjustment to the

fitting of the motor. A dry run,

fitting the motor in place with the screws and loose fitting the worm proved

this to be unnecessary. However, it was

a tip worth remembering.

The

grub screws were tightened on both the worm and gear and power supplied to the

motor just to give it a test spin. So

far so good, but next came the valvegear.

The valve gear was supplied in etched nickle, only the crosshead was a

pewter casting.

The

slide bars were so well designed they just folded up into shape. This was something I was dreading as I had

seen my fathers friends struggle with complicated valvegear on other kits. This all but fell into place, so much so I

had to double check the instructions to make sure I had not overlooked

something just to be sure. The

connecting and coupling rods were all fitted with the nuts supplied. The pickups had already been fitted in place

using low melt solder to secure them to the copperclad circuit boards. Wire could now be run through to the motor

and secured by low melt solder. The

time had come to test the locomotive.

To

my relief the locomotive ran fairly well straight away. A few very minor adjustments were made to

screws, nuts ad the pickups. A very

small amount of oil was applied to the worm and gear and the locomotive left

running against a block for twenty minutes to allow it to bed in.

A

few nights later I was able to take it to the model railway club and give it

it’s first run. It was still unpainted

at this time but at least it worked. I have since painted the locomotive black

using car undercoat and matt black cellulose spray paint. It is necessary to remove the wheels to

paint the locomotive (unless you paint the chassis frames before assembly but I

didn’t think of that.)

To

sum up I have enjoyed building this locomotive kit and am extremely pleased

with the result. An ‘O’ gauge

locomotive kit is not cheap and from what I have seen the quality varies from

one manufacturer to another. The kit I

bought was totally complete, well designed and truly simple to construct. I feel the finished item is something I can

be proud of. Obviously, due to

financial restraints (birthdays once per year and now eagerly awaiting

Christmas…) it will be some time before I can afford another kit but if it

works out as well as this one I will not be disappointed.

Click Here to Return to the

index page index page

|